By: Eric Siegel, Predictive Analytics World

How do computers optimize mass persuasion – for marketing, presidential campaigns, and even healthcare? And why is there actually no data that directly records influence, considering it’s so important? In this season finale episode, Eric Siegel introduces machine learning methods designed to persuade.

Note: This article is based on a transcript of The Dr. Data Show episode, “Persuasion Paradox: How Computers Optimize their Influence on You” (click to view).

How do computers optimize mass persuasion – for marketing, presidential campaigns, and even healthcare? And why is there actually no data that directly records influence or persuasion, considering it’s so important? And what’s the ideal technique for optimizing your dating life and for getting more people to wash their hands in public restrooms? It’s time for Dr. Data’s persuasion paradox “Groundhog Day”-inspired geeksplanation.

Persuasion modeling requires a “deep geek dive” – but it’s as important as it is fascinating.

Of all the things achieved by machine learning, the capability to predict is the Holy Grail for driving decisions in business, healthcare, law enforcement, and more. But predict what, exactly? Like, for targeting marketing, normally it predicts which customers will buy. Then you send, like, a brochure, to those people and only those people, the ones flagged as more likely to buy.

But hold on, a company only want to spend $2 on a glossy sales brochure for consumers it’s likely to persuade. I mean, that’s the whole point of marketing: changing people’s minds. Influencing them. But if I mail everyone predicted to buy, I might be hitting many people who were gonna buy anyway. They don’t need to be persuaded, so it’s a wasted expense, not to mention more paper consumed, more trees cut down. After all, some products just sell themselves; they fly off the shelf even with little-to-no marketing.

A New Prediction Goal: Whether They Will Be Influenced

Ok, so I’ve just convinced myself to change my prediction goal. Instead of using machine learning to predict whether a customer will buy, we’ll predict whether they’d be influenced to buy if they see this brochure. That’s a very different thing to predict.

Woah, that does seem like a great idea. It’s a big change from traditional data driven marketing… And it applies to healthcare, also! If we’re applying a healthcare treatment based on whose health is predicted to improve, we’re making the exactly same mistake as with marketing. ‘Cause, some patients are gonna improve even without treatment. If you take a pill and your headache stops, how do you know it wouldn’t have stopped anyway? And also what about predicting which patients may be hurt by a treatment, those it would actually make worse? It would be better not to treat them at all. So, instead of predicting, will the patient improve with this treatment, predict instead, will the patient improve ONLY with this treatment — and not improve otherwise? Will this treatment itself make a positive change?

Woah, this stuff is kind of confusing, when you think about it.

After all, marketing and healthcare are really quite similar. In both cases you wanna optimally decide who should get the treatment in order to improve the chances of a positive outcome. The whole point of these massive efforts — all the treatments applied across millions of individuals — is to improve outcomes. To have a positive effect on the world, a positive influence. And the best way to decide on a treatment is to predict whether it will have the desired effect on outcome.

Ok, so it’s settled. We’ll use machine learning to generate predictive models that predict not the outcome per se, but instead will predict the influence a treatment would have, for each individual patient or customer. It’ll calculate how much more likely the positive outcome would be for this individual if we apply the treatment.

Ok, great, so all we need is the right dataset for the machine to learn from. Let’s see… normally, we just use the results of a previous marketing campaign, since we’ve tracked who did and who did not buy. With these examples of buy and of not buy, it generates a predictive model that flags who’s likely to buy. So, in order to flag who’s likely to be influenced to buy, we just need examples of some people who were influenced to buy and others who weren’t influenced to buy.

The Dilemma: We Have No Examples of Influence in the Data

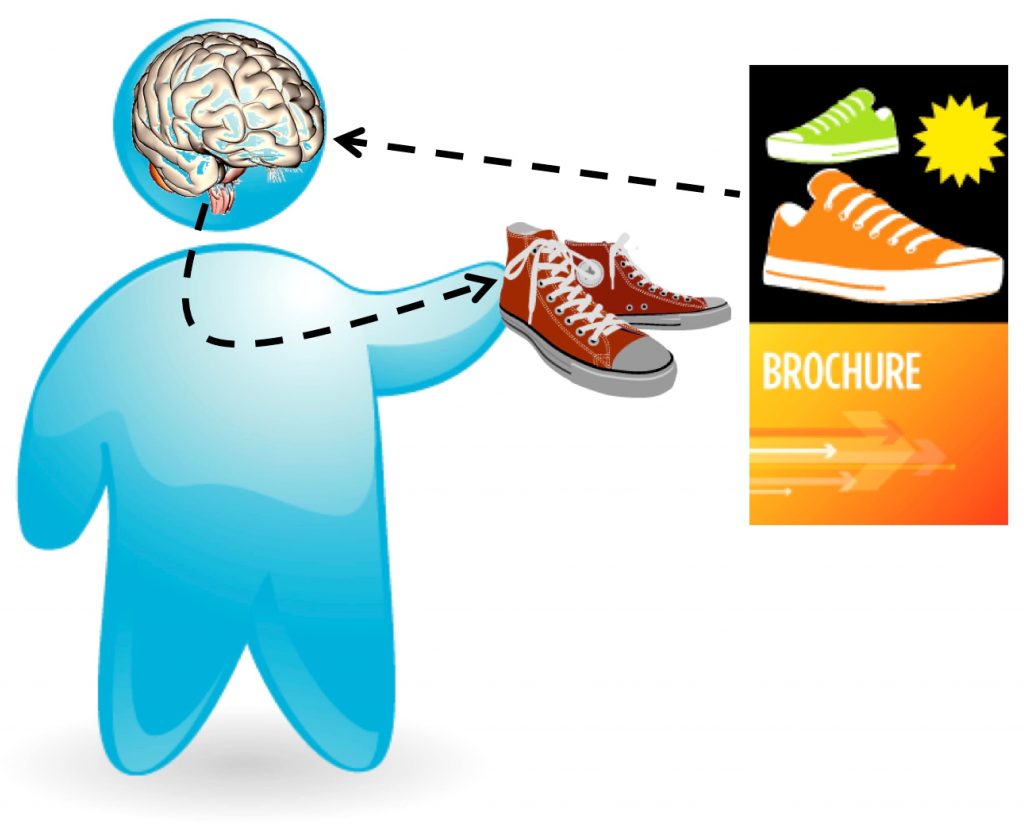

Uhhhhhh… but how can we tracked who was influenced? The only way to know someone was influenced would be if we knew that they would not have bought if we didn’t contact them, that our glossy brochure changed their mind. But we did contact them to find that out, so how could we know what would have happened if we didn’t?

Persuasion takes place in the brain, but the brain is effectively a black box.

We don’t have definitive data on who changed their mind. About anything, related to purchases or any other behavior. After all, how could we? We don’t have brain scanners and, even if we did, our understanding of the brain is severely limited. Well, we could just ask customers by polling them, but we’re trying to use real consumer behavior data the company already has, not spend money on a poll that would get us results about a much smaller sample of customers. And, besides, their responses about whether they were “influenced” will be subjective. I mean, I can’t always be sure about myself — why I bought something – introspection doesn’t tell me for sure what sequence of events would have happened if I had not received that brochure in the mail. Instead, it would be more powerful to make use of existing company data, which essentially observes the spontaneous behavior of consumers in their “natural habitat.” But cases of influence taking place are essentially unobservable.

So, wait a minute — we can’t get data on the one thing we care most about! Influencing people or having some effect on something in the world is the entire point of anything and everything that we do, as individuals and as organizations. I mean, other than meditating to achieve enlightenment, you know what I mean, the functional purpose of your actions is to make some difference.

But each time a person is persuaded or influenced, we can’t be certain about it. It’s an occurrence of causation, which cannot be conclusively observed. To know someone was persuaded, we’d need the answer to two questions:

1) Did the customer purchase after being contacted? And 2) Did the customer purchase even without being contacted?

If the answers to these questions are yes, when contacted, they did buy, and no, when not contacted, they didn’t buy, then we know contacting made a difference. They were influenced. But, if both answers are yes, we know they buy either way – they’re a “sure thing” customer – so the marketing treatment has no influence.

The problem is, you can’t answer both questions because you can’t both contact and not contact the same person. You cannot cleanly, conclusively test for the persuasive power of your marketing material on any one individual. So we can’t observe influence, we can’t collect data about it, and so how can we possibly analyze or predict it?

The Persuasion Paradox: Unknowability

This paradox of unknowability infiltrates even your dating life. How can you optimize your behavior out on a date? ‘Cause, ya know, you’re not in the restaurant for food – it’s a sales call. You’re both the director of marketing and the product. So it’s important to predict which sales or marketing messages will influence the prospect and achieve a positive outcome.

Bill Murray and Andie MacDowell in Groundhog Day

In the movie “Groundhog Day,” Bill Murray is stuck re-living the same day over and over – which he absolutely hates, until he realizes this gives him an unprecedented superpower: He can test different treatments on the same prospect under exactly the same circumstances to see which leads to a positive outcome.

Before proceeding, watch a 47-second clip of the movie.

Do not try that at home. Now, what is Bill Murray trying to predict? Success? The outcome? Whether she’ll fall in love with him? No. He doesn’t care what’s going to happen – he cares what he can do about it. So he’s trying to predict, will this treatment lead to the positive outcome? Unfortunately, we can’t use this technique in real life, ’cause there are no do-overs. Other than, like, in video games. Woot woot!

Measuring Net Influence Across Populations

Well, we can measure influence over a group of people. For example, bathroom signs reminding one to wash their hands increased handwashing – with soap, not counting just rinsing with water – from 50% to 69% in a study conducted by professional researchers lurking in a public bathroom. So the bathroom signs do have a positive influence. But this influence, actually, turns out to only hold for women. With the signs in place, female hand washing increased from 61% to 97%, but men, who were less compliant in the first place, didn’t budge from around 37%.

And thusly we’ve already begun modeling not only how likely one is to wash their hands, but how likely the sign is to influence them to wash their hands. Gender reveals a difference, and if we break down bathroom users into more and more segments by other factors, we could probably become better and better at determining which sign or other reminder would be most influential to each person.

Now, I’m not actually suggesting we install sensors that identify restroom occupants and tailor the message accordingly – I’m just using the bathroom example to illustrate how the plumbing works inside predictive persuasion.

But, for marketing, this is how things work. In fact, slicing and dicing the data to determine how best to influence each individual applies not only for targeting marketing but also for determining healthcare treatments. By the way, slicing it down like that into segments and subsegments is called decision trees – and there are also other more mathematically complex techniques for persuasion modeling as well.

So, as an example on the healthcare side, a certain HIV treatment was shown to more positively influence health for younger children than for other age ranges. And some drugs that treat cancer are so much more effective for people with certain genetic markers that the Food and Drug Administration is increasingly requiring certain genetic screening before they’re prescribed.

Machine Learning for Persuasion: Uplift Modeling

The kind of machine learning that predicts persuasion is known as persuasion modeling or uplift modeling: Generating from data a model that predicts the influence of a treatment.

Instead of what traditional models predict — the future, the behavior, the outcome – like a purchase or an improvement in health – an uplift model predicts a treatment’s influence on that outcome.

For each individual, standard predictive modeling answers the question,“How likely is the positive outcome?” But uplift modeling answers,“How much more likely would the desired outcome be with this treatment?”

After all, the best way to do influence is to predict influence. The most direct way to know whom to market to is to know who is persuadable. Targeting in this way takes a marketing budget or a sales team and makes it more powerful.

In fact, Obama’s 2012 presidential campaign – which, you know, is just another kind of marketing campaign – used uplift modeling and by doing so improved the persuasive power of their $400 million TV ad budget by an estimated 18%, and also significantly improved the effectiveness of campaign volunteers by targeting exactly who’s door to knock on. This helped avoid knocking on the doors of “do-not-disturb” voters, which would actually backfire and inadvertently generate a vote for the opposing 2012 candidate, Romney.

After all, the whole point is to predict not just where there’ll be influence, but, more specifically, where there’ll be positive influence.

Under the right circumstances, uplift modeling improves marketing by a huge margin. Here are all the companies for which I’ve seen public disclosures of that have uplift modeling actually outperforming standard predictive modeling:

- AIG

- Fidelity

- HP

- Intuit

- Lufthansa

- Schwab

- Staples

- Subaru

- Telenor

- US Bank

For Telenor – a big cell phone carrier in Europe – it increased a marketing campaign’s return-on-investment by a factor of 11!

How Uplift Modeling Works

Here’s one little example in marketing of how an uplift model can work. It often turns out that customers who’ve so far bought a medium amount, but not too much – those in the mid-range – are most positively influenced to buy more by marketing contact. The reason for this may be that many who’ve bought nothing at all are harder to get started, and that those who’ve already bought a lot may be negatively influenced – annoyed or otherwise turned off – if you market to them.

Goldilocks

On the other hand, to be honest, most companies are still using standard machine learning, a.k.a., modeling, to predict outcome rather than influence – and in many cases, for good reason. Uplift modeling is more difficult. For training data, it requires the addition of a control set. And the technical methods are less well known, more complex, and more challenging to evaluate.

But I hope you agree it’s an interesting area with great potential. To learn more, check out my other more detailed article on uplift modeling, which ends with a list of links, including the real technical nitty gritty.

This article is based on a transcript from The Dr. Data Show.

CLICK HERE TO VIEW THE FULL EPISODE

About the Dr. Data Show. This new web series breaks the mold for data science infotainment, captivating the planet with short webisodes that cover the very best of machine learning and predictive analytics. Click here to view more episodes and to sign up for future episodes of The Dr. Data Show.